Home Our Nation Heritage

Heritage

Tŝilhqot’in National Government Heritage

The Nation is located between the Fraser River and the Coast Mountains in west-central British Columbia. The relationship that the people have with the territory makes them who they are – the ‘People of the River’. After the spread of smallpox in the 1800s, the Tŝilhqot’in population decreased by 90% by some historical accounts. Today, an estimated 4000 Tŝilhqot’in people live in the territory and across Turtle Island.

About

The Tŝilhqot’in is also the indigenous language spoken by the people through out the territory. Under Tŝilhqot’in dechen ts’edilhtan (literal translation “laying down the stick,” in English or better known as the “law”), the six communities collectively have an inherent responsibility and connection to the entire territory – nen (land) and tu (waters). The Tŝilhqot’in culture, livelihood and governance are inextricably linked to the lands.

The Chilcotin War 1864

The Tŝilhqot’in Nation has long affirmed that their culture and traditional life would be upheld and have asserted full control over their unceded traditional territories. The Tŝilhqot’in territory covers a vast 6,646,593.5 hectares of land.

In 1863, Alfred Waddington began constructing a wagon road through Tŝilhqot’in territory from Bute Inlet to Fort Alexandria to connect to prospects of minerals. The Tŝilhqot’in population had been recently devastated by the 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic and generations believe it to was a purposeful attack to decimate the population and take over the lands.

On April 29, 1864, after members of the Tŝilhqot’in Nation had been working on the road construction faced several injustices such as starvation, lack of payment and a cruel mistreatment to their peoples the Nation waged war with those infringing on their lands (the Chilcotin War of 1864).

While believing that the Tŝilhqot’in Nation was facing peace talks, five Tŝilhqot’in War Chiefs (Tellot, Klattasine, Tah-pitt, Piele and Chessus) were wrongfully arrested and tried for murder. They were further sentenced by Judge Begbie and hung on October 26, 1864 in Quesnel, BC. This is known as the largest public execution in B.C history. The sixth Tŝilhqot’in War Chief (ʔAhan) was later executed in New Westminster in 1865.

The Tŝilhqot’in have long held that this dark history of injustice must be reconciled. After the recognition of Aboriginal title to a portion the territory, the Tŝilhqot’in leadership knew that the next step was to gain recognition of a past of wrongdoings.

As a precondition to reconciliation, the Tŝilhqot’in Nation asserted that B.C. and Canada must exonerate the six Tŝilhqot’in War Chiefs who were regarded as heroes by their people.

On October 23, 2014 B.C. Premier Christy Clark apologized and confirmed without reservation that the six Tŝilhqot’in War Chiefs were fully exonerated of any wrong doing.

Further, on March 26, 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, on behalf of the Government of Canada, exonerated the Tŝilhqot’in War Chiefs. This was a powerful moment with the Tŝilhqot’in Nation being the first Indigenous nation invited on to the floor of the House of Commons. On November 2, 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited Declared Title Lands to deliver the exoneration speech to the Tŝilhqot’in people and recognized the 6 War Chiefs as warriors protecting their lands.

Head Chief Lhats’asʔin

Lhatŝ’aŝʔin Memorial Day

October 26 marks the day that five of the six Tŝilhqot’in War Chiefs were wrongfully tried and hanged in Quesnel, B.C. This day is known as Lhatŝ’aŝʔin Memorial Day to the Tŝilhqot’in people – named after the head War Chief, Nits’ilʔin Lhatŝ’aŝʔin. Every year the event changes location and is held at sites of importance during the Chilcotin War of 1864. The Nation welcomes everyone to attend this important memorial.

Self-determination

On July 25, 2019 the Province of British Columbia, the Government of Canada and the Tŝilhqot’in, guided by the Gwets’en Nilt’i Pathway Agreement (July 25, 2019), aim to resolve jurisdictional issues within the Tŝilhqot’in territory and achieve transformative steps to recognizing the self-determined Tŝilhqot’in as true government partners.

Through this history, the Tŝilhqot’in people have remained strong and resilient. The people were also not immune to the intergenerational trauma caused by residential schools. Williams Lake, a hub city for many Tŝilhqot’in people, is where “Orange Shirt Day” originated from.

The Tŝilhqot’in recognize that the path to self-determination is through jurisdiction and the self-determination of the people.

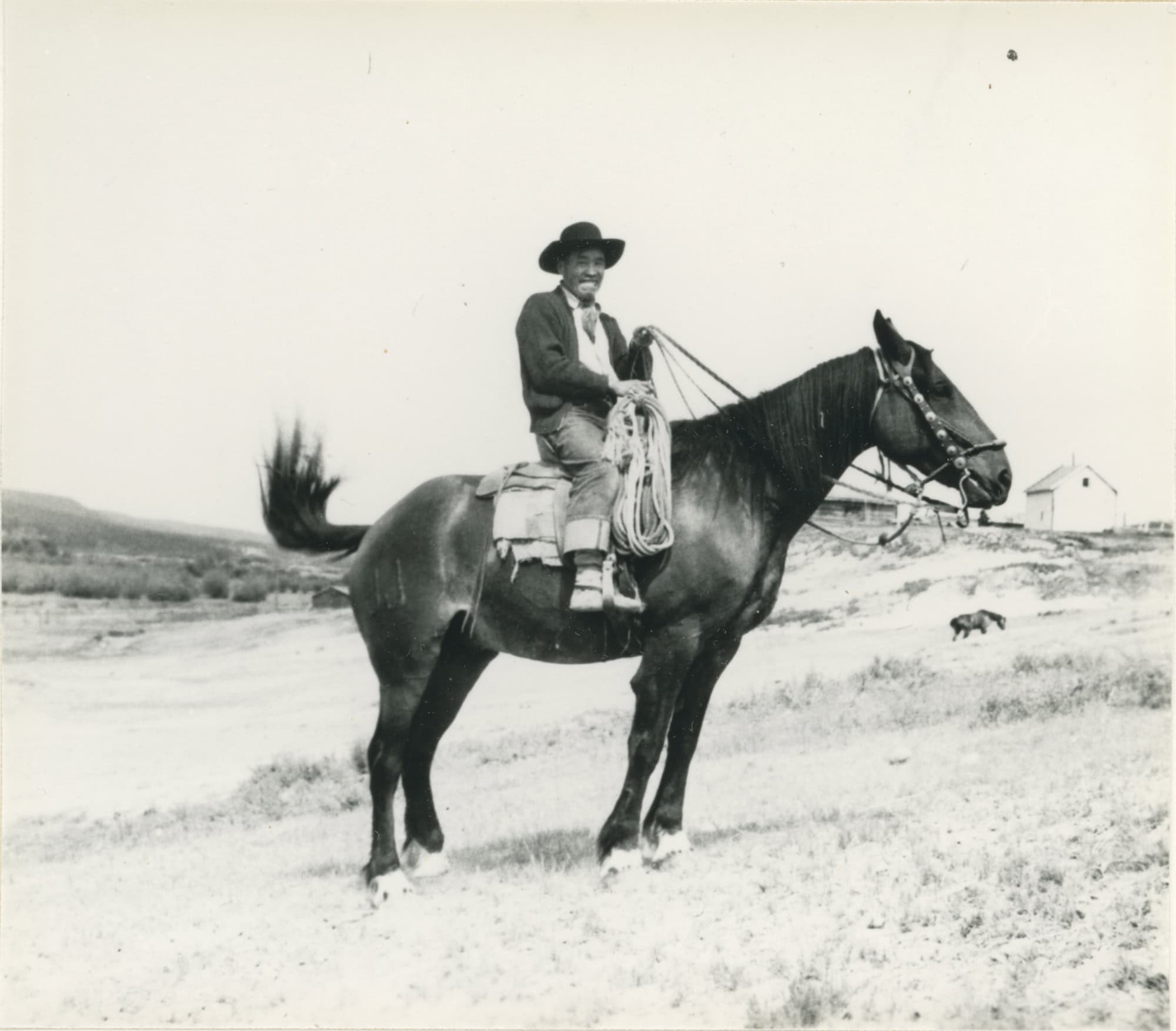

Tŝilhqot’in Rangers on the Chilcotin River

Protection of Tŝilhqot’in Cultural Heritage

From the Chilcotin War of 1864 to the 2014 Supreme Court of Canada victory for Aboriginal title, the Tŝilhqot’in Nation has remained strong, united, and determined to care for ancestral places, to honour our ʔesggidam, and to protect our lands, resources, knowledge, and traditions for future generations. We continue to assert our inherent jurisdiction and authority to control, interpret, protect, and practice our cultural heritage in all its forms.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) and B.C.’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (2019) are examples of a growing recognition for indigenous rights, authority and jurisdiction here and around the world. For Tŝilhqot’in, these shifting attitudes — along with milestone agreements like the Nenqay Deni Accord (2016) and the Gwets’en Nilt’i Pathway Agreement (2019) — are opening new opportunities to improve the management of Tŝilhqot’in heritage for generations to come. Yet as far as we have come there is still much work to do.

In spite of the ongoing challenges we face, our Nation remains united and determined as ever to assert our inherent rights and jurisdiction to improve the way our heritage is understood, protected, practiced, and celebrated.

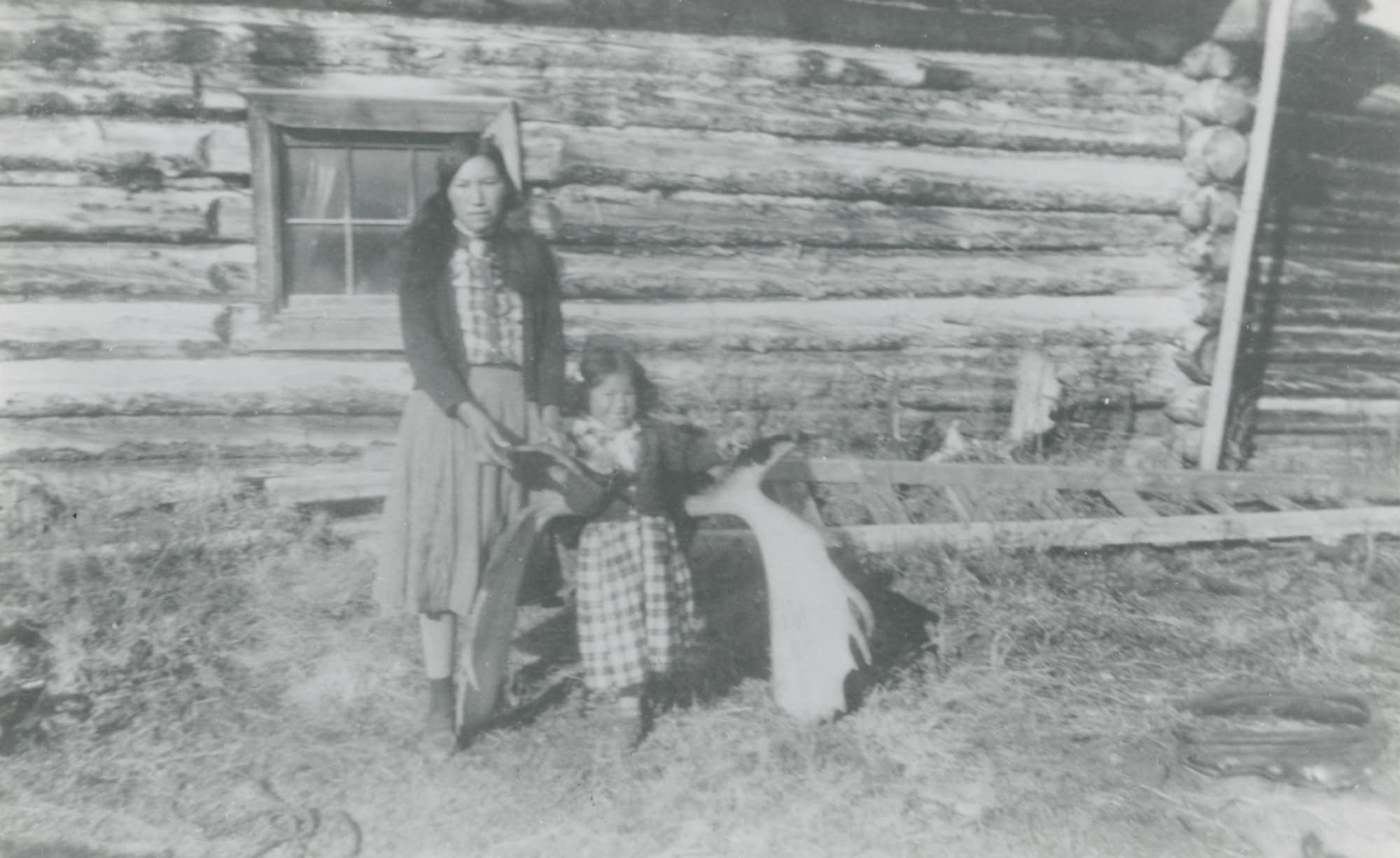

Tŝilhqot’in sharing a drum song

Heritage Resources

- TNG Historical Timeline (June 2023)

- Tŝilhqot’in Territory with place names (Map)

- Chilcotin War Curriculum for Grade 12 (2020)

- Protecting Indigenous Cultural Heritage Resources on Private Land (2023, UVic Law)

- Strategic Plan for the Management of Tŝilhqot’in Cultural Heritage (2022)